I came across this great article by A.V. Lantratov.

It decodes the date embedded in the painting above of Henry Percy, 9th Earl of Northumberland (1564-1632)

A knowledge of astrology/astronomy helps but it’s not vital.

The conclusions are STARTLING to say the least.

As it’s a long piece – I will post it in sections. Also – it has been Googlated from Russian to English so the words are a bit awry but still understandable.

PART 1

Zodiac Henry Percy.

“Elizabethan portrait” of the XX century

A.V. Lantratov

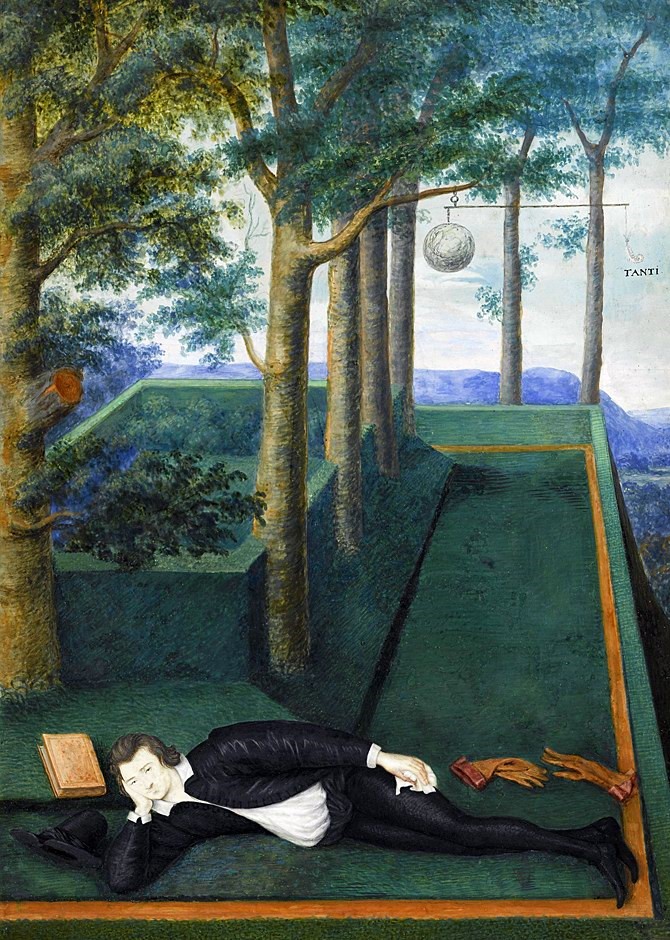

The art collection of the Amsterdam Rijksmuseum holds a small (25.7×17.3 cm) picture, fig. 1, on which, as is commonly believed, the famous English portrait painter Nicholas Hilliard (1547-1619) portrayed one of the famous people of his era – Henry Percy, 9th Earl of Northumberland (1564-1632) and a favorite of Queen Elizabeth I, fig. 2-3.

Fig. 1. Portrait miniature, written, as it is believed, in the years 1590-1595 by

Nicholas Hilliard and, according to historians and art critics, depicting

Henry Percy, 9th Earl of Northumberland. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Fig. 2. Elizabeth Tudor (1533-1603). Portrait by Nicholas Hilliard,

dating from 1573-1575 years. Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool

Fig. 3. Queen Elizabeth in a dress embroidered with armillary spheres,

symbolizing the divine nature of the royal authority. Portrait by

an unknown artist, dating back to about 1580. Private collection

In the most general form in Fig. 1 before us is a young man lying on the grass in a rectangular garden, divided into two parts. Five trees grow inside this garden, and two more trees are seen in the background, beyond the fence.

The question is, what is the meaning of this very unusual composition? On this account, researchers have put forward a number of versions. Thus, the modern domestic art historian A.V. Stepanov reveals it as follows:

“… And another unusual portrait belongs to the brush by Hilliard. Henry Percy, the ninth earl of Northumberland, depicted on it, was nicknamed the Warlock for his enthusiasm for alchemy, cartography, and passion for occult books. Navigator Thomas Harriot lived in the estate of Count Henry, who, sending a Dutch telescope to the sky, was ahead of Galileo in compiling a map of the Moon for several months and was the first in the world to see spots on the Sun. Another friend of the Warlock was John Dee, the famous mathematician, mechanic, alchemist, Kabbalist and clergyman, chief astrologer of Queen Elizabeth (fig. 4 – A. ) …

Fig. 4. John Dee conducts experiments in front of Queen Elizabeth I and her

courtiers. Victorian artist painting by Henry Glindoni

[Warlock], who undoubtedly belongs to the secret design of the portrait, executed by Hilliard … ordered to portray himself lying on a rectangular stepped terrace, raised above the valley, like a tall island above the sea. Here grow trees planted along a ruler, closing up at the top with their dense crowns. The valley and the distant mountains are sunlit. At the top of the terrace, closest to the sun, dark. Count Henry prostrated himself on the ground across the entire width of the portrait, melancholically supporting his head with his hand. The black coat is unbuttoned, the white shirt apache glitters with carelessly tucked into the belt.

“What is the noble lord thinking about?” – the aforementioned AV asks further. Stepanov gives the following answer: “The prospect leads our eyes upwards, where, against the bright sky, a balancer is suspended from a tree b (Fig. 5 – A. ), which could take a place in the treatise of French mechanic Jacques Besson“ Theater of Mathematical and Mechanical Instruments ” (1587) as a parody of the rule of the lever: a moon globe hangs on a short shoulder, a writing pen is hung to a long arm, under which stands the Latin word “tanti” (“equivalent”).

Fig. 5. Balance with globe and pen. Enlarged fragment of fig. one

What does the terrace on which the count dwells in the gloom in broad daylight symbolizes? What is the formula for the trees: 1 x 4 x 2 = 8, or 1 x 3 x 3 = 9, or 2 x 2 x 3 = 12? Or maybe 1 + 4 + 2 = 7? Are these numeric sequences related to John Dee’s numerology? What kind of book is at the head of the graph? Does the globe accidentally correspond with this book, and the pen with a handkerchief, which the count holds in his hand, throwing gloves on the ground? Did the body of the graph accidentally spread parallel to the balance bar? What is equivalent in the head of the count of Northumberland? These questions threaten to plunge us into melancholy, because one of the causes of this disease – obviously a well-known and Warlock – were, according to Robert Burton, “excessive study of science” (Fig. 6-7 – A. ).

Fig. 6. Allegory of Melancholy. Ivory carvings

from Rafael Sadeler’s engraving. Netherlands, the beginning of the XVII century

Fig. 7. Time (in the form of an old man-Saturn) expels Melancholy. Stained glass from Flanders, subsidized approximately 1530 year. Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Whatever the abstruse intent of Count Henry Percy, his portrait is a phenomenon hitherto unheard of in European art. Nicholas Hilliard was the first to introduce a completely new type of person – one to whom no one can impose a norm of behavior that is incompatible with his personal understanding of freedom and comfort. The count-warlock, a friend of the stars, spending the night without sleep in the contemplation of celestial bodies, is betrayed by gloomy reflection at a dizzying height. This image, which recalls the famous engraving of Dürer “Melencolia I” (Fig. 8 – A. ), anticipates, in an unknown manner on the continent, the interest of English romantics toward night and infinity ”, [Stepanov].

Fig. 8. “Melancholy I”. Albrecht Dürer engraving, dating from 1514

So, from this description, we learned that the “Warlock” by Henry Percy was very widely (if not to say overly) an educated person, but hardly came close to understanding the “abstruse intent” presented above, fig. 1 , paintings. Dusk, infinity and melancholy reflecting on the equivalence of the pen to the scarf, and the globe of the book graph …

* * *

Let us turn, therefore, to a different attempt to interpret fig. 1 , undertaken in 1983 by the best specialist in English portrait painting of the Elizabethan era, R.K. Strong, [Strong],

On eight pages of his work, the author highlights the milestones in the history of the painting (we’ll refer to it later), compares it with other works by the same Nicholas Hilliard and contemporary artists, sets out the biography of Henry Percy in search of possible keys to reading the symbolic language of the portrait being analyzed ( direction, this quest develops, we will find out a little below) and, in the end, makes a conclusion.

The latter turned out to be short and fit literally into one line: “Hilliard’s Wizard Earl remains one of the most cryptic hieroglyphs of the Elizabethan age”. Translated into Russian: “[In spite of all the efforts made above] the portrait of the magician-count is still one of the most mysterious symbolic images (literally: hieroglyphs — A. ) of Elizabethan time.”

In the same place, in [Strong] one can read such rather remarkable lines: “Hilliard is obviously painting a highly symbolic program. It’s a bit too early to unravel. ” That is: “The composition depicted by Hilliard is beyond any doubt extremely symbolic [and is a mystery]. Perhaps the time to solve this mystery has not come yet. ”

Thus, even a recognized luminary, by his own admission, could not understand what is actually imprinted on fig. 1 .

What is the matter here? And the matter, as we will further see, is that both of the authors quoted above, successively listing all that is depicted in the picture (garden, trees, balance weight with a feather and a globe, a young man lying on the grass and other details), and noting inevitably attracting the attention of a strange arrangement of trees, immediately set off into lengthy arguments about formulas, numerology, and similar “threatening to plunge us into melancholy” things, but did not guess to do the simplest thing – to count the number of these trees. Namely, in this number, – to which philologist and art historian A.V. Nesterov, – and the main clue is hidden, which makes it possible in the end to correctly read the entire composition of the “mysterious hieroglyph”, fig. 1 .

To Be Continued….