Part 4

Zodiac Henry Percy.

“Elizabethan portrait” of the XX century

A.V. Lantratov

So, of the eight preliminary decisions discussed above, the final inspection left only two dates: November 22, old style, 1801 AD. and November 15th old style 1940 AD The first of them has a significant stretch on the moon, but the second is ideal from an astronomical point of view.

So what happens? In the picture, attributed by Scaligerian historians to the XVI century, and depicting, according to them, the 9th Earl of Northumberland, Henry Percy, is the date from the middle of the 20th century recorded in the middle? Is it really possible? At first glance, it seems that, of course, not, and in front of us is just a random decision, accidentally coinciding with what is depicted in the undoubtedly present antique portrait. Very old. Pure chance. Nothing more. Just “so the stars lay down” (more precisely, in this case, the planet).

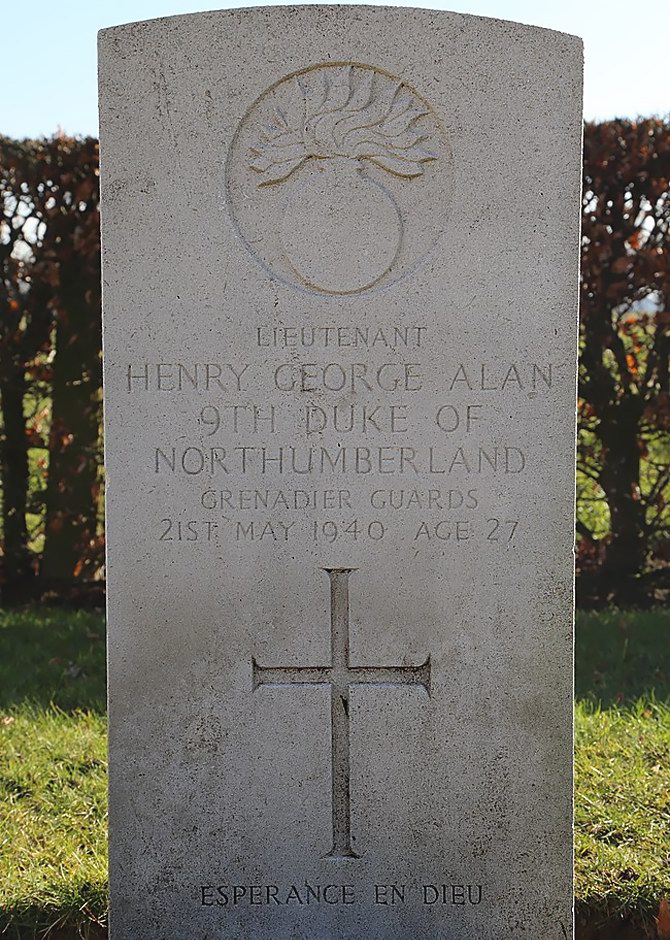

However, the verification of the historical background associated with the 1940 decision presents a completely unexpected surprise. It turns out that literally six months before the date found, namely in May 1940, the 27-year-old 9th (!) Duke of Northumberland (!!), died in one of the battles of the Second World War, known as the Battle of Dunkirk, whose name was … quite right, Henry Percy (!!!), pic. 40-42.

Fig. 40. Henry George Alan Percy (1912–1940),

9th Duke of Northumberland

Fig. 41. A tombstone with the name of Henry Percy at the Esquelmes military cemetery (Esquelmes, Belgium), not far from the Pecq commune, during the defense of which he died

Fig. 42. War memorial in Alnnik (Northumberland county), dedicated to those killed in the First and Second World Wars. Among the names stamped on one of the memorial plates (in the photo is on the left) is: “The 9th Duke of Northumberland” (though for some reason without directly specifying the name)

Let’s read these words again: “Henry Percy, 9th Duke of Northumberland.”

Same name!

Same sequence number!

The same title!

With regards to the latter it is worth making a small explanation. First, the counting of the counts and dukes of Northumberland was interrupted several times and started anew. Therefore, in the history there are at once six people who bore the title of the 1st Earl of Northumberland and four who were called the 1st Duke. And secondly, the current title “Duke of Northumberland” includes the title of the count of the same name, and therefore the duke of Percy was also a count of Northumberland (not counting some other titles, a list of which can be found, for example, in an obituary printed in “The Times”, June 3, 1940: “The Duke of the Eighth Duke …) and the Beatley, Earl of the Neighborhood, Baron Warkworth, Lord Lovaine , and Baron of Alnwick, and created a baronet created by Smithson (now Percy) of Stanwick in 1660, and thus became the head of the family of Percy. He inherited Alnwick Castle, Northumberland, Syon House, Brentford, and Albury Park, Guildford … “).

In other words, the Scaligerian history is immediately known to two ninth earls (dukes) of Northumberland named Henry Percy. One – from the XVI century, when, as we are assured, the picture in question was written with a “symbolic horoscope”, fig. 1 , and the second from the 20th century, when this picture surfaced and was put on display for all to see.

But in this case, it turns out that shown in Fig. 1 “Elizabethan portrait” is a zodiac created almost nowadays, as a tribute to the memory of the recently deceased duke, but for some reason (maybe before the war, he showed interest in Elizabethan painting?) Stylized as a painting of the alleged 16th century.

Naturally, the first (yes, and perhaps not only the first) reaction to such (dictated by strict logic) conclusion is described in textbook words: “This simply cannot be!”. And psychologically this is understandable. In the end, in the same way, the majority of people, at least during their initial acquaintance with HX, perceived the idea that everything, to put it mildly, in Scaliger’s chronology from childhood, is not right, to say the least. Therefore, let us once again carefully look at “one of the most mysterious” English portrait miniatures, pic. 1 , and let us see how these or other details (and all of it as a whole) correspond to the conclusion that follows from the dating that we are dealing with, not with a lifetime portrait.

Let’s go through all the points.

1) First of all, the age of the deceased Duke Percy – 27 years old – perfectly corresponds to the age of the person captured in the picture.

2) In addition, the latter, as already mentioned, is represented as lying in a kind of “Zion garden”, that is, already deceased.

3) Further, in the above description of the picture given in [Nesterov], the following words are included: “The dark robe of the graph suggests the” colors of Saturn “associated with melancholy.” But Saturn is also associated with death, fig. 29 .

4) In addition, attention is drawn to very pale – almost white – the skin color (and especially the face) of the image. Obviously, this can also be interpreted as a hint that the latter has already died, and it is not he himself who appears before us, but his soul, who is at this moment somewhere in the afterlife. The same idea is also suggested by the “gloom in broad daylight,” which is mentioned in [Stepanov].

5) A closed book lying at the head of a young man may quite transparently hint at a closed book of life (therefore, there is no title on its cover), that is, again indicate death.

6) In the same, posthumous perspective, the meaning of the white scarf compressed by the person depicted in the picture can be explained. If you look closely, you can see that the outline of this shawl is somehow reminiscent of a lamb that has bent one paw (and you can see its head between your thumb and index finger). Something similar can be seen on a variety of images of the Lamb of God, fig. 43

Fig. 43. Lamb-like handkerchief in the portrait of Henry Percy

Fig. 43. Lamb-like handkerchief in the portrait of Henry Percy

(enlarged fragment of Fig. 1, left). On the right, by comparison, is the

Lamb lying on the book of Revelation (a fragment of a stained glass window from

St. Sebastian ’s Church in the town of Chikasso, Alabama, USA)

But the Lamb of God is a symbol of Christ, the suffering and death of the one who atone for the sins of all people and who brought them the possibility of salvation. In this context, this allusion may clearly indicate that the deceased sacrificed himself in order to save others. And such an interpretation exactly corresponds to the essence of the matter, since the Dunkirk operation, at the very beginning of which the Duke Percy died, was to evacuate from the continent a three hundred thousandth group of forces of the English expeditionary corps, French units and remnants of the Belgian forces locked on the coast. That is, literally, Percy, like the lamb of Christ, gave his life to save many others.

7) A fairly clear indication of the posthumous nature of fig. 1 can also be seen in the pose itself, in which the portrayed one is shown, since it is this (lying, with the hand under the head) that is characteristic of many memorial images, fig. 44-48.

Fig. 44. A memorial portrait of Sir Henry Anton (Unton, 1557-1596), the

Fig. 44. A memorial portrait of Sir Henry Anton (Unton, 1557-1596), the

work of an unknown artist. “The adviser to the queen, the soldier, the ambassador, the

hospitable host of the estate — all of these, like so many of the other roles of

Sir Henry that he had to play during his life, are at once

represented in the picture, somewhat resembling iconic living

with stamps” [Nesterov]. National Portrait Gallery, London

Figure 45. Sir Henry Anton’s Tombstone. Enlarged fragment of fig. 44

Figure 46. Family tomb family Fettipleys in the Church of St. Mary in Swinbrook (Oxfordshire). The left row of tombstones dates from 1613, the right – 1686 year

Fig. 47. The tombstone of William Fettipleis (1533-1562)

Fig. 48. Memorial lawyer and politician, member of the House of Commons

Fig. 48. Memorial lawyer and politician, member of the House of Commons

Chaloner Shyut (1595-1659) in the estate Vine (Hampshire)

8) Another very interesting point to which attention should be paid is that the young man depicted in the picture lies exactly under the sawn on the tree closest to the viewer, that is, exactly where the sawed off branch should have been. In other words, it turns out that he (or rather, as we already understand, his soul) is symbolically correlated with the sawed-off branch of this tree. And since it represents the Sun itself, it turns out that the artist skillfully emphasized, on the one hand, the high origin (the solar branch) of the figure, and on the other, his heroic (the branch did not fall away, she was sawed off) death.

9) Finally, the enclosed rectangular courtyard in fig. 1 can symbolize not only the Libra constellation, but also the mass grave in which the duke Percy is buried, fig. 49.

Fig. 49. Mass grave, in which the remains of Henry Percy are buried.

Fig. 49. Mass grave, in which the remains of Henry Percy are buried.

A relatively small, enclosed by a low hedge,

courtyard, behind which trees grow, in general, is very similar

to what is depicted by the artist in Fig. one

Thus, we see that the contents of fig. 1 really is best read through the prism of his posthumous nature.

So, above we were convinced that nothing from the image on fig. 1 does not contradict his dating. But how then, it is asked, to be with the fact that the picture in question, as already mentioned above, was twice put up for auction at a date previously allegedly recorded on it (in 1937 and 1940)?

To find out, we turn to the relevant auctions, or rather to the auction catalog of Frederick Muller, held in April 1940 (that is, a month before the death of the Duke Percy), available in the electronic library of the National Institute of Art History, Paris, [Beets], fig. 50.

Fig. 50. Title page of the catalog [Beets]

In total, this catalog contains 482 items, and the portrait of Henry Percy is listed as number 66. Although not, not so. At number 66, it means “the portrait of Sir Philip Sidney” (which, as someone later somehow established, is in fact a portrait of Henry Percy), pic. 51.

Fig. 51. Description of the portrait of “Sir Philip Sidney, dreaming

against the backdrop of a beautiful landscape”, now known as the portrait of

Henry Percy. Fragment of one of the pages of the [Beets] catalog

However, this is not important. The important mark is “voir la reproduction”, which means that in the annex to the catalog there is a photo of the corresponding picture (however it is called). Indeed, scrolling through this application, we will see a photo of exactly that picture, which today is called the portrait of Henry Percy, pic. 52.

Fig. 52. A page from the [Beets] catalog with a photograph of a

Fig. 52. A page from the [Beets] catalog with a photograph of a

portrait of Henry Percy (aka Philip Sidney’s portrait)

So what? It seems to be the official version of the history of the painting, according to which it was sold before the death of the Duke Percy, passed the test, and we have no choice but to conclude that, despite the whole chain of amazing coincidences, we still made a mistake and all from start to finish was a waste of time and effort? However, not everything is so simple, and together with the photo confirming the version offered to us, there is a bright oddity.

The fact is that if you carefully review the entire application, it is impossible not to notice that the order in which the illustrations are placed in it, in general, corresponds to their catalog numbers. With one notable exception. Which, as you might guess, is the portrait of Philip Sidney (he is the portrait of Henry Percy). His picture is not placed at the beginning of the application, as one would expect, but at the very end, after number 343 (despite the fact that the portrait of Sidney / Percy, as already mentioned, has number 66), fig. 52 .

And now the mechanism of “legalization” of the freshly written picture (and its transformation from the portrait of Henry Percy, who died in the 20th century, into the portrait of Henry Percy, who lived three centuries earlier) becomes completely transparent.

In fact, auction catalogs are editions with extremely small circulation (if we talk specifically about the [Beets] catalog, it is unlikely that it could exceed several dozen copies) and intended for a very limited circle of people. After the auction is completed, almost all of them remain in the hands of visitors, and literally a few copies are placed in storage in the largest specialized libraries, so that they can be accessed by the appropriate specialists.

In such conditions, all that had to be done was to print a couple of (ten possible, for maximum reliability) “corrected” copies, including a photo of the desired picture, and replace them with original copies in those libraries whose services are used by the most reputable art historians and auction workers. On the question of the reason for the replacement, it was possible to refer to the correction of the defect made during the initial printing. In case someone overly meticulous checks old and new instances and notices a discrepancy, you can answer in the same way: they were in a hurry, time was running out, they didn’t see, they were to blame, they decided to correct, they wanted to do better … Well, if it was necessary to apply an administrative resource, so to speak, then it would hardly have been difficult, given what kind of family are we talking about. However, a modest reward would be enough for those who tactfully took their eyes aside at the right time and “noticed nothing” (especially since there was a war in the yard, and the majority were not up to scruples).

Thus, in the particular case under consideration, the presence of a photograph of the desired picture in the catalog, published allegedly no less than six months before the date we calculated it, cannot be considered a reliable proof of the latter’s fallacy.

And in this regard, another extremely curious story deserves consideration.

* * *

As we saw above, presented in Fig. 1 portrait contains a number of fairly transparent indications that it is a memorial, that is, it is posthumous. However, there is another version of the same picture, shown below in fig. 53.

Fig. 53. The second (in the full sense of the miniature, 5.2×6.4 cm in size)

version of the portrait of Henry Percy, which is considered a copy, made from Fig. 1

by the same Nicholas Hilliard (previously, however, it was attributed to his pupil

Roland Loki) and attributable to 1595. Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

On the one hand, the extreme similarity of both miniatures is undoubted, and it is quite clear why both of them are now attributed to the brush of the same master. On the other hand, the general attitude of fig. 53 strikingly different from fig. 1 . And the matter, of course, is not in a noticeably smaller size or another form. No, the matter is in the atmosphere creating details.

First, in fig. 53 there is no dark background, “twilight in broad daylight,” and that pallor on the face of the figure that was so striking when looking at fig. 1 . Secondly, the book lying on its headboard in fig. 1 was closed; in fig. 53 , on the contrary, it is revealed (and it is clear that something is written in it). Third, the strict black frock coat rice. 1 was replaced on rice. 53 on a lighter, covered with patterns, an even greater metamorphosis occurred with a white shirt. Finally, fourthly, the grass in the meadow, on which the figure lies, has become much lighter in comparison with fig. 1 , and, in addition to this, a multitude of white, yellow and red flowers grew on it, rice 53 .

In short, the version of the portrait in Fig. 53 much more “live”, than on fig. 1 . And the question arises, which of them was written earlier? Yes, according to modern historians and art historians rice. 53 is a copy from fig. 1 , but on what basis did they make this conclusion? On that pic. 53 significantly smaller in size and therefore, most likely, was copied from a larger original? Indeed, this logic in itself is quite convincing, but it does not at all follow from it that the exact original was just fig. 1 , and not some other, now lost, picture.

In a word, it is clear that no matter how we compare rice. 1 and fig. 53 among themselves, an exhaustive answer to the question of which of them was written earlier and which later would not be possible. Therefore, let us ask ourselves another question: which of these two paintings was the first to “come to light”, that is, it was published and became available to scientists and anyone interested in art?

With a miniature from the Rijksmuseum, pic. 1 , we have already sorted out the details above, and all that remains to be added is that it actually comes into the view of the scientific community, apparently, not earlier than 1961, when her photo was first published in a solid (and entirely dedicated to Nicholas Hilliard) A 350-page monograph by the German art historian Erna Auerbach, referenced in [Cummings]. Until then, the history of this miniature is very dark and more than doubtful.

And what about the Cambridge option? The site of the Fitzuilyama museum itself states only that the museum acquired it at Christie’s auction in 1953, and the earlier story is set out in a very concise manner, and even so in a presumptive way (Percy, Leicester, Captain Bertram Currie, his sale Christie’s 27 March 1953 (23), where he bought for the Museum ”).

Judging only by this date, it turns out that the Cambridge miniature emerged from the dark depths of private collections much later than the Amsterdam one (allegedly put up for auction thirteen years earlier), and therefore, as modern historians believe, is secondary to it. However, if you look at the literature list cited there, then we will find the Williamson edition published in 1904 (it is, by the way, that the reference is given in the description of Fig. 51 ), which , if opened, will be able to find a photo of the miniature Cambridge

Thus, a reliable segment of the history of the Cambridge version of the portrait of Henry Percy begins much earlier than that of the version from Amsterdam.

And here it would be possible to assume that it was looking once at fig. 53 and comparing it with fig. 1 historians finally understood that the identification of the latter with the portrait of Philip Sidney in the [Beets] catalog, pic. 51 , was erroneous, and they returned to him the old, correct name. Here only a hitch that, as a miniature on fig. 53 was also previously considered a portrait of Philip Sidney. And not Henry Percy. Just like a portrait of Philip Sidney, she is described in [Williamson].

As a result, we again return to the question already asked earlier: how was it established that both portraits do not depict Philip Sidney, but Henry Percy? There are no inscriptions on them. Heraldic images too. Visual comparison of facial features also does not allow to draw the appropriate conclusion. And, for that matter, much greater similarity is found when comparing Fig. 53 not with other portraits of Henry Percy (from the 16th century), fig. 36 , fig. 37 or Philip Sidney, pic. 31 , Fig. 32 , and with an unidentified young man on one of the miniatures of Isaac Oliver, fig. 54-55.

Fig. 54. Anthony-Maria Brown, 2nd Viscount Montague (1574-1629)

Fig. 54. Anthony-Maria Brown, 2nd Viscount Montague (1574-1629)

surrounded by brothers John and Williams, as well as an unidentified

visitor to the miniature of Isaac Oliver, dating from 1598.

Picture gallery of Burley House Manor (Lincolnshire)

Fig. 55. Philip Sidney (aka Henry Percy, left) and an unknown guest of the Brown family (right). Enlarged fragments of fig. 53 and fig. 54

So how did historians and art historians learn that it was Henry Percy who was in front of them? Found the above entry in the diaries of J. Vertyu? But, even without going into finding out how much this record can be trusted, neither the size of the picture nor its form is indicated in it, but the description is so succinctly laconic that it can be referred to the good ten (if not more) of the remaining pictures dating back about the same time.

However, if we are to be thoroughly attentive to the details, even in such a brief description there is a contradiction with the version we are suggesting. In fact, we will read once again what exactly is written in J. Virtyu’s diary: “Lord Percy, lying on the grass in the gardens of Zion, died around 1585” (“a Lord Percy and on the ground, dyd about 1585. Syon Gardens, [Strong]). “He died around 1585”! But “about 1585,” he died not the 9th Earl of Northumberland, but his father, rice. 34 . And he lived to 1632. That is, according to J. Vertyu, who indicated this date (or the owners of the house, with whose words he wrote it down), the picture he saw was depicted not the 9th, but the 8th Earl of Northumberland.

It would seem, well, what’s the difference, the 8th or 9th, if the 8th graph was also called Henry Percy? And the difference is that with such identification depicted in Fig. 1 young people are beginning to wobble strongly (not to say they instantly crumble into dust) all the constructions of modern art critics tied to “mystery”, “diagrams and geometric forms … loaded with symbolic and Pythagorean meanings” and other “Renaissance occultism in its hermetic and kabbalistic izvod “. Not to mention the attempt of the author [Nesterov] to “solve the puzzle” pic. 1 , comparing it with the horoscope of the 9th Earl of Northumberland instead of the horoscope of the 8th …

* * *

But, no matter how it was, by now we have figured out quite enough to understand which scheme most likely the events developed.

So, by the beginning of the 20th century, a miniature was known, which was considered a portrait of Philip Sidney, fig. 53 . Then, in 1940, at the Frederick Müller auction, some other miniature was sold, apparently with a more or less similar plot and, most likely, the same name. After some time, this miniature was either processed, fig. 56, or was replaced by a completely new, written from scratch, but in the same “old” “Elizabethan” style.

Fig. 56. One of the surviving portraits of Queen Elizabeth (left)

Fig. 56. One of the surviving portraits of Queen Elizabeth (left)

and a fragment of her radiographs (right), which clearly shows

that the picture originally depicted a completely different woman

(there is a version that she could be Anna Boleyn).

National Portrait Gallery, London

After that, of course, certain manipulations followed to provide the “new old” picture with a more or less solid and reliable-looking history, as well as proper (however, deliberately unverifiable) references to archival documents. And finally, as a result of all efforts, the new (or edited old) picture, which must perpetuate (in the form understandable only for a narrow circle of initiates), the memory of an outstanding representative of one of the most distinguished English families, was solemnly issued as a portrait of Henry Percy, pic. 1 . But not that Henry Percy, who died a heroic death in a war, rice. 40 , fig. 41 , fig. 42 , and the one who was a hero at the time of Queen Elizabeth I, the most popular in England,rice 36 , fig. 37 .

* * *

True, one more question remains: why was the above discussion constantly going on only about the 1940 auction, whereas, according to legend, the picture in question was also exhibited three years before, at the Christie auction held in 1937? The answer is: firstly, the search for the catalog of the corresponding auction was not crowned with success. And secondly, even if someone manages to find a copy of it, in which the picture of a picture now stored in Amsterdam, fig. 1 , it will not at all testify in favor of its authenticity (and, accordingly, the fallacy of the astronomical dating we received), as one might think. On the contrary, it will indicate an obvious fake catalog.

Indeed. We already know that in 1904 [Williamson] was published, containing a photograph of that version of the portrait of Henry Percy, which is now kept in the Fitzuillama Museum in Cambridge, pic. 53 . Moreover, it was not a thin pamphlet, released in a circulation of ten pieces and instantly settled in private libraries. No, these were two volumes of a rather large format, a total of four hundred pages (half of which, however, fell on illustrations of hundreds of portrait miniatures), published in half a thousand copies. And in this edition, as we, again, already know, fig. 53 was signed as a portrait of Philip Sidney. And as such – a portrait of Philip Sidney – he remained both until the time of the Christie auction in 1937, and for some time afterwards.

Accordingly, if at Christie’s auction in 1937, exactly what we see today, looking at fig. 1 , then this picture would have to have the same name – a portrait of Philip Sidney. However, in fact, a certain “portrait of an unknown young man” went under the hammer!

Of course, to explain this screaming contradiction, we can try to suppose that the [Williamson] edition, despite its circulation, was left to very few people, and was not quoted at all in the auction environment. But this is already refuted by the fact that the experts of the auction house of Frederick Muller, who compiled the [Beets] catalog, knew about it very well and referred to it, fig. 51 . It is obviously not necessary to count Christie’s experts as less knowledgeable in their professional field.

But maybe, by 1937, some of the venerable art critics had doubts that in fig. 53 (and, therefore, in Fig. 1) Philip Sidney is depicted, and therefore the compilers of the Christie catalog chose the most neutral name (they say, let it be a “portrait of the unknown” and then the experts will figure it out among themselves)? No, this is also excluded. First, if such doubts really existed, then, following professional ethics, they would be obliged to inform them (for example: “a miniature traditionally regarded as a portrait of Philip Sidney; at the same time, expert X recently put forward a different version … “). Secondly, the same doubts would be reflected in the later [Beets] catalog. Finally, thirdly and mainly, from the point of view of auction logic, the portrait of the “famous” (whether it is good or bad, whether it is good or bad) is always better than the portrait of the unknown, because the first is connected to the story, for touching which to a large extent

Thus, everything indicates that whatever picture was sold in 1937, it could not be the same one that later turned out to be in the Amsterdam Rijksmuseum, Fig. 1 .

* * *

Of course, it is possible, in spite of everything, to declare that absolutely everything described above is just a series of curious (sometimes even very curious), but nothing meaningful coincidences. But then it turns out that just somehow, by itself, it turned out that in 1940, being the year of the only astronomical ideal solution shown in Fig. 1 horoscope, a certain Henry Percy died, the 9th Duke of Northumberland, whose name, title, and even the serial number of which quite coincidentally coincided with those of a man, according to modern scholars, captured long ago on the “very, very old” picture. Which, again, by the pure whim of the case, carries in itself a mass of references, read through the “memorial prism”.

Are there too many accidents?

Well, and the last is a rather obvious question that has remained unresolved: why in fig. 1 recorded the date of November 1940, while the duke Percy died six months earlier? Surely, several factors played a role at once. For example, mourning among relatives and friends and their awareness of the loss of the head of the house could go on for a very long time. However, the main reason, most likely, was that in November the Sun (related in Fig. 1 with the Duke of Percy) was in Scorpio, that is, in the constellation of death. In other words, the date for the zodiac ciphered in the picture was chosen so as to (together with all the details listed above) emphasize its “afterlife” symbolism as much as possible.

Before turning to the conclusion, let us return briefly to the symbolic language of fig. 1 and consider another interesting point that does not affect the already received dating of the picture, but allows deeper revealing of its astronomical meaning.

Namely, we look again at the balance weights symbolizing Libra constellation, fig. 14 , on one end of which a silver ball (moon globe) is suspended, and on the other – a bird feather (more precisely, two feathers, one of which is almost not noticeable), fig. 15 .

The question is, why did the author of the picture, after all, presented the moon in such a completely unusual way? Of course, by and large, it is quite enough and already given the above explanation, which consists in the fact that he simply artistically beat the two visible phases of the lunar cycle – the full moon (ball / globe) and a thin sickle (feather) of the old moon. Naturally, equal to each other (after all, the Moon itself, when and where you look at it, remains the same) and therefore balances each other on improvised weights. All this is completely obvious and understandable. But still … Is there any additional subtext here?

Apparently, such a subtext really exists, and it is the astronomical dating of the encrypted in fig. 1 horoscope.

The fact is that on the date found above – November 15, old style (November 28, new style) of 1940, the Moon was visible in the sky for the last time before a new moon (its phase was 0.02 at dawn on November 28, 1940, and decreased to 0 , 01 by the sunset of the same day; the next morning it was already exactly 0.00). But just before the new moon, before disappearing from the observer’s eyes, the Moon (in the northern hemisphere of the Earth) has the form of a thin sickle, directed by “horns” to the right, that is, it looks exactly as it is shown in the picture, fig. 15 .

In other words, it turns out that the artist depicted the moon exactly as it was observed on the date we found – in the form of a thin crescent-feather. And in order to make it clear that this feather symbolizes not something else, but a night light, he placed the moon globe next to it (and the word “equal”).

Moreover, taking into account the above considerations, even such a seemingly completely small and random detail, such as the fact that at the right end of the “lunar” rocker is depicted, if you look closely at it, not one, but two feathers, the first of they can be seen well, whereas the second is literally barely noticeable, fig. 15 It is difficult to get rid of the impression that in this way the creator of the picture in question gracefully beat the very process of the onset of the new moon, which consists in the gradual final disappearance of the already barely visible moon crescent. Indeed, the upper part of the “big” crescent, consisting of two feathers, dissolves with a weakening of the gaze, and only the “small” crescent that has shrunk in half remains visible, and soon the new moon will disappear. In other words, the master who worked on the picture managed to find a beautiful solution that allowed him to portray exactly what was observed on the desired date in an incomparably more artistic form than by drawing just a crescent or a solid black circle.

By the way, the image next to the “moon” feather of the globe may have, besides underlining their equivalence (“tanti”), and one more interesting explanation. Namely, let us pay attention to the fact that, in itself, this globe, which is quite obvious in the context under consideration, also corresponds to a fully illuminated (as opposed to a pinch sickle) Moon. But after all, on the date we found, as already mentioned, it was almost a new moon, and there were still a fortnight before the full moon. How to combine it? The easiest way is to assume that the artist simply depicted two opposite phases, the one in which the moon was at the time of the horoscope, and the one she was to go into, thereby emphasizing their circulation. But then the question arises: which of the two phases shown should be considered the “main” one? That is, that which corresponds to the date recorded in the picture. Yes, of course, from the solution we found, it follows that the right one is the “feather” phase. But from the very image,rice 15 , it does not follow. There is some uncertainty. The question is, can it be eliminated?

The answer is yes you can. The fact is that there is an optical phenomenon called the ash light of the moon, which consists in the fact that shortly before (and soon after) the onset of a new moon, the moon can be observed entirely, despite the fact that only a small part of it is illuminated by the sun. The mechanism of this phenomenon is well known: the illumination of the surface of the Moon, unlit by direct sunlight, is formed by sunlight scattered by the Earth, and then again reflected by the Moon to the Earth. At the same time, the part of the lunar surface unlit with direct sunlight has a characteristic ashen color, fig. 57.

Fig. 57. The ash light of the moon. Bright sickle – part directly

Fig. 57. The ash light of the moon. Bright sickle – part directly

lit by the sun. The rest of the moon is illuminated by light

reflected from the earth.

It is probably this phenomenon that is reflected in fig. 1 in the form of a silver (i.e. ashen) ball. And then the contradiction noted above is removed, and the artistic symbolism of the new moon outlined earlier begins to play with even brighter colors than before.

So, as we see, presented on fig. 15 moon symbolism (with a globe, a feather and a balance), if you look at it through the prism of the dating of the horoscope depicted in the picture, we get very clear, bright and literally saturated with astronomical meaning.

It becomes even clearer if we compare it with the allegorical-hermetic interpretations mentioned at the very beginning. For example, such: “something so intangible and ephemeral as royal favor (feather – A.) can balance the whole weight of [the person opposed to the person depicted in the portrait] of the world (ball – A.)” (“something as insubstantial and ephemeral as royal favor can balance the weight of the rest of the world “, [Strong]; and there is also a whole paragraph in this spirit).

Or like this: “What does the terrace symbolize on which the count dwells in the gloom in broad daylight? What is the formula for the trees: 1 x 4 x 2 = 8, or 1 x 3 x 3 = 9, or 2 x 2 x 3 = 12? Or maybe 1 + 4 + 2 = 7? Are these numeric sequences related to John Dee’s numerology? What kind of book is at the head of the graph? Does the globe accidentally correspond with this book, and the pen with a handkerchief, which the count holds in his hand, throwing gloves on the ground? Did the body of the graph accidentally spread parallel to the balance bar? What is equivalent in the head of the count of Northumberland? These questions threaten to plunge us into melancholy … ”, [Stepanov].

Well, as far as the found reading is better than the one proposed by the author [Nesterov] – no one at all – there is no need to say.

* * *

In conclusion, in fig. 58-60 are three examples of truly allegorical images of scales.

Fig. 58. Thomas Chaloner (1521-1565), statesman and poet,

Fig. 58. Thomas Chaloner (1521-1565), statesman and poet,

with allegorical weights, symbolizing the superiority of knowledge

over all the riches of the world. Portrait by an unknown artist,

dated 1559. National Portrait Gallery, London

Figure 59. Knowledge (left) and Wealth (right) on the scales of Life. Enlarged fragments of fig. 58

Figure 60. A feather is stronger than a cannon (when looking at this drawing, Mavro Orbini’s words involuntarily come to mind: “Some fought and won, while others wrote a story”). Illustration from the book of emblems: Henry Peacham, Minerva Britanna …, 1612

- Conclusions

- The portrait miniature in the Amsterdam Rijksmuseum, considered to be one of the most mysterious English portraits created in the era of Queen Elizabeth Tudor, and depicting, in the opinion of modern historians and art historians, the 9th Earl of Northumberland, Henry Percy, on closer examination, the bizarre, but, nevertheless, amenable to independent deciphering and unbiased astronomical dating of the horoscope.

- The corresponding calculations, as well as an analysis of the circumstances connected with the history of this picture, in no way confirm the Scaligerian dating of the time of its writing by the end of the 16th century. On the contrary, they clearly show that the date of November 15 of the old style (November 28 of the new style) of 1940 is recorded on it. Different from the declared three hundred and fifty years.

- It turns out and the true identity of the person to whom the mysterious “Elizabethan” miniature was actually dedicated. He turns out to be the heroically deceased lieutenant of the British royal guard, Henry Percy, who also bore the title of 9th Duke of Northumberland during World War II.

- From all this, it follows that even in the most recent time (and, one can be sure, it continues to occur so far) the falsification of some published (and therefore seemingly “certainly very reliable”) historical documents. For example, the auction catalog of F. Muller of 1940 (and also, possibly, of the catalog of Christie of 1937), where a photo of a picture created (at least in the form available today) was introduced after the auction, but slyly identified ( most likely, in order to give it a long and solid history) with one of the paintings sold at this auction, allegedly under the “wrong” name.

- In addition, it turns out that the ancient tradition of creating zodiacs containing the hidden, intended only for a narrow circle of initiates, the meaning survived at least until the middle of the last century.

Literature

[НХЕ] Nosovsky G.V., Fomenko A.T. “New chronology of Egypt. Studies of 2000-2003. – Moscow, “Veche”, 2003.

[DZ] Nosovsky G.V., Fomenko A.T. “Ancient Zodiacs of Egypt and Europe. Dates of 2003-2004. – Moscow, “Veche”, 2005.

[ERIZ] Nosovsky G.V., Fomenko A.T. “Egyptian, Russian and Italian zodiacs. Discoveries 2005-2008. – Moscow, Astrel, ACT, 2009.

[BAT] Nosovsky G.V., Fomenko A.T. “Vatican. (Astronomy Zodiac. Istanbul and the Vatican. Chinese horoscopes. Research 2008-2010) “. – Moscow, Astrel, ACT, 2010.

[INK] Nosovsky G.V., Fomenko A.T. “The Incas came to America from Russia-Horde. England was also an Horde colony “, – Moscow, Astrel, ACT, 2018

[Beets] «Collection du Docteur N. Beets a Amsterdam. La vente aux encheres publiques les 9, 10 et 11 avril 1940 Frederik Muller & Cie dans le grande salle des ventes de la maison “. – Amsterdam, 1940.

[Cummings] Cummings F. “Boothby, Rousseau, and the Romantic Malady”. – The Burlington Magazine, Vol. 110, No. 789, 1968, pp. 659-667.

[Strong] Strong RC “Nicholas Hilliard’s miniature of the” Wizard Earl “.” – Bulletin van het Rijksmuseum, Jaarg. 31, No. 1, 1983, pp. 54-62.

[Williamson] Williamson GC “The History of Portrait Miniatures.” 1531-1860. Volume I. – London, 1904.

[Nesterov] Nesterov A.V. “Wheel of Fortune. Representation of man and the world in the English culture of the beginning of the New time ”. – Moscow, Progress-Tradition, 2015.

[Stepanov] Stepanov A.V. “Art of the Renaissance. Netherlands. Germany. France. Spain. England”. – St. Petersburg, ABC-Classic, 2009.

(article received 12/27/2018)

(the final dating of the zodiac reviewed in this paper was obtained jointly with GV Nosovsky and AT Fomenko)