Holinshed’s Chronicles (1577) – often referred to as just ‘Holinshed’ – is a large collaborative work describing England, Scotland, Ireland and their histories from their first inhabitation to the mid-16th century. The work was a principal source for many literary writers of the Renaissance, including Marlowe, Spenser, Daniel and Shakespeare.

In 1548, the prominent London printer and bookseller Reyner (or Reginald) Wolfe ambitiously decided to produce a universal history and cosmography (i.e. description and mapping) of the world. After Wolfe’s death in 1573, his assistant Raphael Holinshed took over the project, hired more writers and restrained its scope to the British Isles. The Chronicles was first published in 1577 in a two-volume folio edition, illustrated with numerous woodcuts. After Holinshed’s death in 1580, Abraham Fleming published the significantly expanded and revised second edition of 1587 in a larger folio format, this time without illustrations.

Shakespeare and Holinshed

Shakespeare used Holinshed as a source for more than a third of his plays, including Macbeth, King Lear and the English history plays such as Richard III. He used it in a range of ways, sometimes following the text of the Chronicles closely, even echoing its words and phrases; sometimes using it as an inspiration for plot details; and at other times deviating from its account altogether, either preferring other sources or his own imagination. Comparing Shakespeare’s plays to Holinshed and other sources can provide rich insight into his creative intentions and processes, as well as giving us an idea of some of the context in which Shakespeare’s contemporary audiences would have understood his plays.

It is widely believed that Shakespeare used the 1587 edition of Holinshed, based on similarities between some of Shakespeare’s text and passages which only appear in the later edition.

Holinshed as a source for King Lear

Shakespeare loosely follows Holinshed’s account of Leir, a legendary king of Britain whose story is set in roughly the 8th century BCE. The main differences are that in Holinshed, Leir’s eldest daughters are married to the Dukes of Cornwale and Albania after the love test and that Leir decrees only half of his kingdom is to be assigned to the Dukes immediately, the rest to be divided at his death. The Dukes rise up against Leir and take control of the other half by force, allowing the King a small maintenance which, with the support of Gonerilla and Regan, is gradually diminished. Leir flees to Gallia (France) where Cordeilla gives him money for clothes and attendants, receiving him at court with all the honour of a king. Cordeilla is renamed as Leir’s sole heir and she and her husband Aganippus raise an army and restore Leir to the throne, killing the Dukes. Leir rules for two years before he dies and the throne passes to Cordeilla. She rules for five years, but after the death of Aganippus, Margan and Cunedagius – the sons of Gonerilla and Regan – rise up against her, refusing to be ruled by a woman. Cordeilla is taken prisoner and, in despair of regaining her liberty, kills herself. There follows a period of civil war.

One of the key similarities to Holinshed is the emphasis on the naturalness of Cordeilla’s love for her father, and the unnaturalness of Gonerilla and Regan. Lear’s madness in King Lear, as well as his death and the murder of Cordelia, seem to be Shakespeare’s invention.

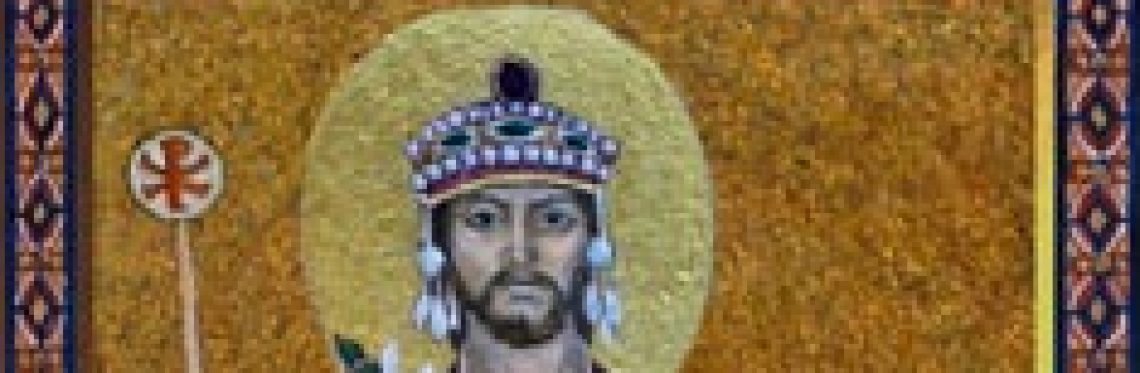

The text for the story of Leir and Cordeilla is very similar in both editions of Holinshed with changes restricted to spelling or phrasing. As well as the text of the Leir story, the 1577 edition also has woodcut illustrations of Leir as a warrior king wearing armour and of Cordeilla, shown both as a queen and a despairing suicide.