Issue

November 6 , 2007

About Dating the Silver Codex (Codex Argenteus)

Yordan Tabov

Institute of Mathematics and Computer Science,

BAS tabov@math.bas.bg

The article analyzes specific details from the history of Codex Argenteus from the mid-16th century, when it came to the attention of the public in the form of a manuscript in the Benedictine monastery in Verdun, until 1669, when it was presented to Uppsala University. On this basis is the hypothesis that Codex Argenteus, stored in the library of the named university, is a list from the original Verdun manuscript, and that this list was made in the XVII century, most likely around 1660.

Goths and the Silver Bible

Among the historical monuments of the distant past that have survived to this day, there are real treasures. These include the astonishing, admirable, and awe-inspiring beautiful manuscript – “Silver Bible”, Silver Codex or Codex Argenteus (in short SB, SK or CA), whose silver and gold letters are on purple parchment ( Figure 1) are of very high quality are a symbol and carrier of the achievements of the ancient warlike and courageous people ready. Its strict beauty makes a deep impression, and its mysterious history, the beginning of which modern science dates back to the V century, far from us, makes anyone, from an amateur amateur to a specialist and from an apologist of the old German culture to her critic, respect and write about her with respect .

Among the historical monuments of the distant past that have survived to this day, there are real treasures. These include the astonishing, admirable, and awe-inspiring beautiful manuscript – “Silver Bible”, Silver Codex or Codex Argenteus (in short SB, SK or CA), whose silver and gold letters are on purple parchment ( Figure 1) are of very high quality are a symbol and carrier of the achievements of the ancient warlike and courageous people ready. Its strict beauty makes a deep impression, and its mysterious history, the beginning of which modern science dates back to the V century, far from us, makes anyone, from an amateur amateur to a specialist and from an apologist of the old German culture to her critic, respect and write about her with respect .

The prevailing point of view in science links the Silver Code with the translation of the Bible by the Gothic preacher and enlightener Ulfila in the 5th century, and argues that the language of this text is ancient Gothic, spoken by the Goths, and the code itself – parchment and beautiful letters – is made in VI century at the court of the Gothic king Theodorich.

However, there have been scientists who reject certain aspects of this theory. Opinions have been expressed more than once that there is no sufficiently convincing reason to identify the language of the Silver Code with the language of the ancients, just as there is no reason to identify its text with a translation of Ulfilah.

The history of the Goths during the time of Ulfila is connected with the territories of the Balkan Peninsula and affects the history of the Bulgarians, and a number of medieval sources testify to the close relations of the Goths with the Bulgarians; therefore, a critical attitude to the widespread theory of the Goths was reflected in the writings of Bulgarian scholars, among which the names of G. Tsenov, G. Sotirov, A. Chilingirova are worth mentioning. Recently, Chilingirov compiled a collection of “Goti and Geti” (CHIL), containing both his own research and excerpts from the publications of G. Tsenov, F. Shishich, S. Lesnoy, G. Sotirov, B. Peychev, which presents a number of information and considerations , contrary to the prevailing notions of origin and history of the Goths. The line of departure from tradition in modern research in the West is noted by the work of G. Davis DAV.

Recently, criticism of a different nature has appeared, denying the old origin of the Silver Code. W. Topper, J. Kesler, I. Schumach came up with reasoned opinions that the UK is a fake, created in the XVII century. A particularly important argument in favor of this statement is the fact indicated by J. Kesler that the “ink” that could be used to write “silver letters” in CA could be born only as a result of the discoveries of Glauber, who lived in the eighteenth century.

But how to combine this criticism with the fact that, according to the prevailing opinion about the Code, it was discovered in the middle of the XVI century, long before the birth of Glauber?

The search for the answer to this question, ending with the corresponding hypothesis, is described below.

It is natural to begin our analysis by examining information about when and how the Silver Bible was discovered, and what happened to it before it got to its current place at the University Library in Uppsala.

Uppsala version

Uppsala University (Sweden), in whose library Codex Argenteus is stored – this sacred symbol for Swedes and Germanic peoples, is the main center for Codex research. Therefore, the views of local scholars there on the history of the Codex are very important, defining components in line with the prevailing theories about the Codex. On the library website of this university we find the following short text:

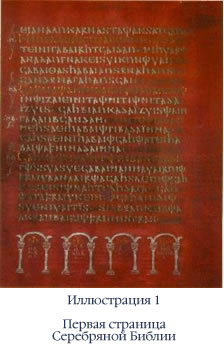

“This world-famous manuscript is written in silver and gold letters on pink parchment in Ravenna around 520. It contains fragments of the four Gospels of the” Gothic Bible “by Bishop Ulfila (Wulfila), who lived in the fourth century. Of the original 336 sheets, only 188 remain. One sheet, found in 1970 at the Speyer Cathedral in Germany, is all kept in Uppsala.

The manuscript was discovered in the middle of the 16th century in the library of the Benedictine monastery in Verdun in the Ruhr region, not far from the German city of Essen. Later it became the property of Emperor Rudolph II, and when in July 1648, the last year of the Thirty Years War, the Swedes occupied Prague, the manuscript fell into their hands along with the rest of the treasures of the imperial castle of Hradchani. Then she was transferred to the Queen Christina Library in Stockholm, but after the Queen’s abdication in 1654, she fell into the hands of one of her librarians, the Dutch scientist Isaac Vossius. He took the manuscript with him to Holland, where in 1662In 1669 the Duke gave the manuscript library at Uppsala University, having previously ordered a silver cover, made in Stockholm artist David klokera Erenstralem ” 1 . (Lars Munkhammar MUNK1; more on this in an article of the same author MUNK2)

pay particular attention to some important details for us:

1) It is considered established – with an accuracy of up to about ten years – the manuscript production time: about 520 g.

2) CA was the Four Gospels, from which individual fragments reached us.

3) It is believed that the text of CA goes back to the text of the Gothic translation of the Bible, made by Ulfilah.

4) The fate of CA is known since the middle of the XVII century, when it was discovered in Verdun, near the city of Essen.

5) Later CA was the property of Emperor Rudolph II – until 1648, when it fell into the hands of the Swedish invaders of Prague.

6) The next owner of CA was Queen Christina of Sweden.

7) In 1654, the manuscript was handed over to Isaac Vossius, the librarian of Queen Christina.

8) In 1662, Vossius sold the manuscript to the Swedish Duke Magnus Gabriel De la Garde.

9) In 1699, the Duke presented the manuscript to the library of Uppsala University, where it is still stored.

For the purposes of our study, it would be useful to find out: how is it known that the manuscript was made in Ravenna, and how is it concluded that this happened about 520 g?

The cited story gives the impression that since the middle of the XVII century, or at least since Rudolph II, the fate of the manuscript can be traced quite clearly. But nevertheless, questions arise: have lists been made from her for all this time? If so, what is their fate? And in particular, could Codex Argenteus not be a list from a manuscript seen in the middle of the 16th century. in Verdun?

Bruce Metzger’s version

Now let’s look at a more detailed story about SA, reflecting the prevailing opinion about its history. He is owned by renowned Bible Translation Specialist Bruce Metzger.

“A century after the death of Ulfila, the Ostrogothic leader Theodoric conquered Northern Italy and founded a powerful empire, and the Visigoths already owned Spain. Considering that the Goths of both countries, judging by the surviving evidence, used it, it was obviously widespread in large parts of Europe. Undoubtedly, many manuscripts of the version were created in the schools of scribes of Northern Italy and other places in the 5th-6th centuries, but only eight copies survived, mostly fragmentary. ., oskoshny instance of large-format, written on purple vellum with silver ink, and in some places gold. Not only this, but also the artistic style, and the quality of the miniatures and decor indicate that the manuscript was made for a member of the royal family – perhaps for King Theodorich himself.

The Ostrogothic state in Italy did not last long (488-554) and in the middle of the 6th century. fell in bloody battles with the Eastern Roman Empire. The surviving Goths left Italy, and the Gothic language disappeared, leaving almost no trace. Interest in Gothic manuscripts completely disappeared. Many of them were dismantled into sheets, the text was washed away, and expensive parchment was used again to write texts that were in demand at that time. The Silver Codex is the only surviving Gothic manuscript (except for a double sheet with Gothic and Latin text found in Egypt), which passed this sad fate.

Codex Argenteus (Silver Codex) contains the Four Gospels, written, as was said above, on purple parchment with silver, sometimes gold ink. From the original 336 sheets in the format 19.5 cm long and 25 cm high, only 188 sheets have been preserved – one sheet was discovered recently, in 1970 (see below). The Gospels are arranged in the so-called Western order (Matthew, John, Luke, Mark), as in the code from Brescia and other manuscripts of the Old Latin Bible. The first three lines of each gospel are written in gold letters, which makes the code especially luxurious. Gold ink is written and the beginning of the sections, as well as abbreviations of evangelical names in four tables of parallel places at the end of each page. Silver ink, now darkened and oxidized, is very poorly read on dark crimson parchment. In the photo reproduction, the text of the Gospels of Matthew and Luke is very different from the text of John and Mark – possibly because of a different composition of silver ink (the ink used to write the Gospels of John and Mark contained more silver).

What happened to the Silver Code in the first thousand years of its existence remains a mystery. In the middle of the XVI century. Anthony Morillon, Secretary of Cardinal Granwell, discovered the manuscript in the library of the Verdun monastery on the Ruhr, in Westphalia. He rewrote the “Prayer of the Lord” and several other fragments, which later along with other rewritten verses were published by Arnold Mercator, the son of the famous cartographer Gerhard Mercator. Two Belgian scholars, Georg Cassander and Cornelius Wooters, learning about the existence of the manuscript, drew the attention of the scientific community, and Emperor Rudolph II, a lover of works of art and manuscripts, took the codex to his favorite castle of Hradcany in Prague. In 1648, in the last year of the Thirty Years War, the manuscript was sent to Stockholm among trophies and presented to the young Queen of Sweden Christine. After her abdication in 1654, her learned librarian, the Danish Isaac Vossy, bought a manuscript that set off again when Vossy returned to his homeland.

Finally, the manuscript was lucky: a specialist saw it. Uncle Vossia Francis Junius (son of a theologian from the time of the Reformation with the same name) thoroughly studied the ancient Teutonic languages. In the fact that his nephew provided him with a study of this unique document, Junius saw the finger of Providence. Based on a transcription made by a scholar named Derrer, he prepared the first printed edition of the version of the Gospels of Ulfilah (Dordrecht, 1665). However, even before the publication was released, the manuscript again changed its owner. In 1662, it was bought by the Supreme Chancellor of Sweden, Count Magnus Gabriel de la Hardy, one of the most famous Swedish aristocrats, the patron of art.

The precious manuscript almost died when the ship that brought it back to Sweden, with a strong storm, skirted one of the islands in the Zeider See Bay. But good packaging saved the code from corrosive salt water; The next trip on another ship was successful.

Fully aware of the historical value of the manuscript, in 1669, de la Guardi handed it over to the library of the University of Uppsala, ordering a magnificent handmade silver salary for the court smith ( Illustration 2.). In the library, the manuscript became the subject of thorough study, and in subsequent years several editions of the codex were published. Impeccable from a philological point of view, the publication, with wonderful facsimiles, was prepared in the 19th century. A. Uppstrom (Uppstrom; Uppsala, 1854); in 1857 it was supplemented with 10 pages of the Gospel of Mark (they were stolen from the manuscript between 1821 and 1834, but returned by the thief on his deathbed).

Figure 2. Silver salary of the Gothic Bible.

In 1927, when Uppsala University celebrated its 450th anniversary, a monumental facsimile edition was published. A group of photographers, using the most modern reproducing methods, created a set of sheets of the entire manuscript, which are even easier to read than the darkened parchment sheets of the original. The authors of the publication, Professor Otto von Friezen and Dr. Anders Grape, then the librarian of the university, presented the results of their study of the paleographic features of the codex and the history of its adventures over the centuries.

The romantic story of the fate of the manuscript was replenished with another chapter in 1970, when during the restoration of the chapel of St. Afras in Speyer Cathedral, the diocesan archivist Dr. Franz Huffner found in a wooden reliquary a leaf, as it turned out, from Codex Argenteus. The sheet contains the ending of the Gospel of Mark (16: 12–20) 1184. A notable option is the lack of the Gothic equivalent of the sacrament ![]() in verse 12. The word farwa (image, form) in the same verse was supplemented by the then known Gothic Wortschatz. “(METS)

in verse 12. The word farwa (image, form) in the same verse was supplemented by the then known Gothic Wortschatz. “(METS)

From this text we learn, first of all, how the experts determined the date and place of manuscript production: this is done on the basis that CA is a “luxurious large-format copy written in purple parchment with silver ink and, in some places, gold. Not only that, but both the artistic style and the quality of the miniatures and decor indicate that the manuscript was made for a member of the royal family – perhaps for King Theodorich himself. “

In general, this is a correct argument, although it would be reckless to immediately agree that the king for whom the manuscript was made is precisely Theodorich. For example, both Emperor Rudolph II and Queen Christina would be suitable for the role of this ruler – if Codex Argenteus is a list from the Verdun manuscript.

Further, it turns out that lists from the Verdun manuscript began to be made from the very moment of its discovery: Anthony Morillon, who found it, copied the “Prayer of the Lord” and several other fragments. All this, along with other transcribed verses, was published by Arnold Mercator. Later, the text of Codex Argenteus was used by Francis Junius; based on it, he prepared the publication of versions of the Gospels of Ulfilah.

In this connection, another question arises: To what extent can the text of the Silver Code be associated with the Ulfilov translation of the Bible? It is important because, as is known from a large number of information, Ulfil was an Arian, and his translation should reflect the characteristics of Arianism.

And here an important feature of the CA text is revealed: it practically lacks Arian elements. Here is what B. Metzger writes on this subject:

“From a theological point of view, Ulfilah was inclined towards Arianism (or semi-Arianism); the question of how his theological views could influence the translation of the New Testament and whether there was such an influence at all was much discussed. Perhaps the only a certain trace of the dogmatic tendencies of the translator is found in Philip 2: 6, where the pre-existence of Christ is spoken of galeiko guda (“similar to God”), although the Greek ![]() should be translated ibna guda. ” (Metz)

should be translated ibna guda. ” (Metz)

Therefore, if the CA text goes back to the translation of Ulfila, then it is almost certainly carefully censored. His “cleansing” of Arianism and editing according to Catholic dogma could hardly have happened in Ravenna during Theodoric. Therefore, this version of the four Gospels almost certainly cannot come from the court of Theodoric. Therefore, CA cannot be so closely connected with Theodorich, and his dating is the first half of the 6th century. freezes in the air, devoid of reason.

But still it remains unclear: were there Arian features in the text of the manuscript found in Verdun? And were there any attempts to eliminate such features, if they really existed?

Metzger’s version complements the list of people who played an important role in the history of Codex with two new names for our study: Francis Junius, a connoisseur of ancient Teutonic languages and uncle Isaac Vossius, and a scholar named Derrer, who transcribed theCodex text for the first printed edition of the Gospels of Ulfila ( Dordrecht, 1665).

Thus, one key fact has been clarified for us: between 1654 and 1662, a list was made from the Verdun manuscript.

Kesler version

Codex Argenteus became a symbol of the Gothic past, not only because it is, as Metzger writes, “the only surviving Gothic manuscript (except for a double sheet with Gothic and Latin text found in Egypt)” (METs), but also largely due to its impressive appearance : Magenta parchment on which the text is written and silver ink .

Such a manuscript is really not easy to produce. In addition to expensive parchment of good quality, you need to color it with purple, and silver and gold letters seem something exotic.

How could the ancient Goths do all this? What knowledge and technology did their masters have to do such a thing?

However, the history of chemistry shows that they could hardly have such a technology.

J. Kesler writes about purple parchment that “the purple color of the parchment with its head reveals its nitric acid treatment” (CES p. 65) and adds:

“Chemical materials science and the history of chemistry suggest that the only way to implement such a silver letter is to write the text with an aqueous solution of silver nitrate followed by reduction of silver with an aqueous solution of formaldehyde under certain conditions.

Silver nitrate was first obtained and studied by Johann Glauber in 1648-1660. For the first time, the so-called “silver mirror” reaction was carried out between an aqueous solution of silver nitrate and “ant alcohol,” that is, formalin — an aqueous solution formaldehyde rum.

Therefore, it is completely logical that the “Silver Code” was “discovered” precisely in 1665 by the monk F. Junius in Verdun Abbey near Cologne, since they could start its production no earlier than 1650. “(CES p. 65)

In support of these conclusions, J. Kesler also refers to the ideas of W. Topper that the Silver Code is a fake made in the late Middle Ages (CES p. 65; TOP). Kesler’s rationale is described in more detail on p. 63-65 CES books; in fact, we find the same opinion in the work of I. Shumakh SHUM, where the author adds that “… all existing medieval manuscripts on purple parchment should also be dated after 1650” (SHUM), and that this applies, in particular, to the aforementioned A. I. Sobolevsky “Purple parchment, with gold or silver letter, known in Greek manuscripts only VI-VIII centuries” (SOB). Excerpts from the work of I. Schumach,Appendix 1 . The reaction of the “silver mirror” and the preparation of the purple dye are described by Alexei Safonov in Appendix 2 .

However, in the above quote with Kesler’s reasoning, there is an inaccurate statement that the Silver Code was “discovered” in 1665 by the monk F. Junius in Verdun Abbey.

In fact, the evidence suggests that as early as the middle of the sixteenth century a certain manuscript was noticed in Verdun Abbey, which we will later call the “Verdun manuscript” and abbreviate BP. Later, she was in the hands of Emperor Rudolph II. Then, having changed several owners and “made a trip” to several cities in Europe, the Verdun manuscript turned into a “Codex Argenteus”, which was donated to Uppsala University. Moreover, in modern science it is implied that the Verdun manuscript is the “Codex Argenteus”; and, what’s the same, “Codex Argenteus” is nothing but a Verdun manuscript,

Critical remarks and considerations by Topper and Kesler conclude that “Codex Argenteus” is a fake .

However, this conclusion ignores the existence of BP and denies its possible connection with SA.

In this study, we accept both the existence of BP and its possible association with SA. But at the same time, Kesler’s arguments should be taken into account. And it follows from them that the manuscript found in Verdun Abbey in the middle of the sixteenth century could hardly have been Codex Argenteus. As a result, the hypothesis that CA was created after the middle of the 17th century begins to take shape; that it is a list (possibly with some modifications) from the Verdun manuscript; that it was made after the middle of the 17th century. and that later the role of the Verdun manuscript was attributed to him. When exactly and how could this happen?

The first thought that comes to mind is that the substitution occurred when the manuscript was in the hands of Vossius.

Version of Kulundzhich

In his monograph on the history of writing, Zvonimir Kulundzhich writes the following about the Silver Code:

“Among the bibliographic rarities of medieval scriptories there are rulers of letters and whole codes written on painted parchment sheets. These include the very famous and considered most valuable” Codex Argenteus “written in Gothic letters … Codex pages are purple and the whole text is written in silver and in gold letters. Of the original 330 sheets of the codex by the year 1648, 187 remained, and all of them have survived to this day.This codex was created in the 6th century in Upper Italy. from Italy and Verdun. It is known that around 1600 it was the property of the Emperor of the German Holy Roman Empire Rudolph II, who at the end of his life lived in Hradchani near Prague, where he studied alchemy and assembled a large library. When the Swedish general Johann Christoph Königsmark captured Prague during the Thirty Years War, he took the code and sent it as a gift to the Swedish Queen Christina. In 1654, this code passed into the hands of the classical philologist Isaac Vossius, who lived at the court of Christina for some time. In 1665, he published in Dordrecht the first printed edition of our Codex. But even before the publication of this first edition, the manuscript was bought by the Swedish Marshal Count de la Guardie, who ordered a silver binding for her and then presented it to the Queen.

In this story, new details are very important for our study.

Firstly, the word “alchemy” appears . It should be borne in mind that at that time chemical knowledge was accumulated precisely within the framework of alchemy, and that all scientific discoveries, including the discoveries of Glauber, took place there. Alchemist Johann Glauber first obtained and studied silver nitrate, he also conducted the so-called. the reaction of the “silver mirror”, as noted above in the Kesler version, and thereby has a direct relation to the “silver ink”, i.e. to create ink with which you can write “silver” letters. Such letters

Secondly, the Swedish commander Johann Christoph Königsmark, who captured Prague during the Thirty Years War, sent BP as a present to the Swedish Queen Christina.

Thirdly, the Swedish Marshal Count de la Guardie bought BP from Vossius and, ordering a silver binding for her, gave it to the Queen.

Fourth, the SA was donated (in 1669) to the University Library in Uppsala Cristina, and not by Marshal Count de la Guardie.

All these actions raise a lot of questions. For example: how did BP fall into the hands of Vossius? Why did Marshal Count de la Guardie present the Queen with a book that belonged to her before? And why, having accepted the gift, the queen gave it to Uppsala University?

Only details can help us at least partially understand this story, and we will turn to them.

Alchemy and Rudolph II

Prague in the sixteenth century was the European center of alchemy and astrology – writes P. Marshall in his book about Prague during the Renaissance (see MAR article on the book). It became thanks to Rudolf II, who at 24 years old received the crown of the king of Bohemia, Austria, Germany and Hungary and was elected emperor of the Holy Roman Empire and soon after that he transferred his capital and his court from Vienna to Prague. Among the hundreds of astrologers, alchemists, philosophers and artists who went to Prague to enjoy the chosen society were the Polish alchemist Michael Sendigovius, who in all likelihood is the discoverer of oxygen, the Danish aristocrat and astronomer Tycho Brahe, the German mathematician Johannes Kepler, who discovered the three laws of planetary motion, and many others (MAR). Among the interests and occupations of Emperor Rudolph II, one of the most important places was occupied by alchemy. To indulge her, heturned one of the towers of his castle – the Powder Tower – into an alchemy laboratory (MAR).

“Emperor Rudolph II (1576-1612) was a philanthropist of wandering alchemists – according to the Great Encyclopedic Dictionary of Brockhaus and Efron – and his residence was the central point of alchemical science of that time. The emperor’s favorites called him the German Hermes Trismegistus.” Rudolph II was named

“King of the Alchemists” and “patron of the alchemists” in the article “History of Prague” (TOB), where the author, Anna Tobotras, gives the following explanations:

“At that time, alchemy was considered the most important of the sciences. The emperor was engaged in it himself and was considered an expert in this field. The basic principle of alchemy was faith, drawn from the Aristotelian teachings on the nature of matter and space and Arab ideas about the properties of certain substances, which, combining 4 elements – earth, air, water and fire – and 3 substances – sulfur, salt and silver – it is possible, under exact astronomical conditions, to obtain the elixir of life, the philosopher’s stone, and gold. Many were completely captured by this search or to extend their own life and, or in search of power. Many others have proclaimed that they can get it. Thanks to the support of the emperor,

Thus, falling into the hands of Rudolph II at the end of the XVI century, BP became the property of the alchemist. Subsequently, she changed her owner several times, but, as we will see later, she stayed in the society of alchemists for more than half a century. And it’s quite difficult and not accidental alchemists …

Kristina, Queen of Sweden (1626-1689)

“When the Swedish commander Johann Christoph Königsmark captured Prague during the Thirty Years War, he took the code from Hradcany Castle and sent it as a gift to the Swedish Queen Kristina,” – we read in the version of Kulundzhich cited above.

“When the Swedish commander Johann Christoph Königsmark captured Prague during the Thirty Years War, he took the code from Hradcany Castle and sent it as a gift to the Swedish Queen Kristina,” – we read in the version of Kulundzhich cited above.

Why did Koenigsmark send Queen Christine a gift from a captured Prague book? Were there other treasures more interesting to the young woman?

The answer to this question is very simple: Queen Christina ( Figure 3 , AKE1) was interested, and she was engaged in alchemy for almost all her life. The Verdun manuscript is only one of Rudolph’s manuscripts, which was in Christine’s hands. She was the owner of a whole collection of alchemical manuscripts, previously owned by Emperor Rudolph II. They became the prey of the Swedish army after the capture of Prague. Most likely, it was they who were interested in the queen, and therefore, probably, they were an essential part of the gift of general Königsmark Christine, and the Verdun manuscript, along with other books, appeared in their company by chance.

So Queen Christina was interested in Isam was engaged in alchemythroughout almost his entire life. She was also occupied with theories about the mystical origin of the runes. She was familiar with Sendivogius’ vision of the rise of the “metal monarchy of the North.” In this regard, hopes for the active role of Christine in this process were expressed by the alchemist Johannes Frank in his treatise “Colloquium philosophcum cum diis montanis” (Uppsala 1651).

Christina had about 40 manuscripts on alchemy, including reference books on practical laboratory work. The names of their authors include, for example, the following: Geber, Johann Scotus, Arnold de Villa Nova, Raymond Lul, Albertus Magnus, Thomas Aquinas, George Ripley, Johann Grashof.

Her collection of printed books totaled several thousand volumes. There is a document in the Bodelyan Library in Oxford that contains a list of Christine’s books. A document with this content is also in the Vatican Library.

In 1654, Queen Christina abdicated and moved to Rome. Her interest in alchemy has increased; in Rome, she acquired her own alchemical laboratory and conducted experiments .

All this information about Queen Christina is taken from an article by Susanna Ackerman AKE1, containing the results of her many years of research on the life path and activities of Queen Christina. In it S. Akerman also cites another fact that is extremely important for the problems of interest to us: Queen Christina was in correspondence with one of the most famous and talented alchemists of that time – with Johann Rudolph Glauber, who, in a sense, was the discoverer of silver ink technology and “purple parchments . ” The most interesting excerpts from Article C in terms of the silver letters of the Codex Argenteus

.

Isaac Vossius

After visiting the library of Queen Christina for several years, the Verdun manuscript was transferred to her librarian. S. Ackerman writes that in 1655 the queen

“… gave a large collection of alchemical manuscripts to her librarian Isaac Vossius. These manuscripts were previously owned by Emperor Rudolf II and were in German, Czech and Latin. The collection itself is now called Codices Vossiani Chymici at Leiden University. ” (AKE1; see Appendix 3 )

Elsewhere (AKE2; see Appendix 4) S. Ackerman explains that the alchemical manuscripts from the Rudolph collection were given to Vossius as a payment for his services: during his stay at the Queen’s court, he had to work on creating the Academy in Stockholm, whose goal was to study the eastern foundations (background) The bible. But the money for this undertaking ran out, and when Christina abdicated, she paid Vossius for the work of books. More precisely, in 1654 she sent manuscripts and books along with other collections to Antwerp on the ship Fortune (Destiny), and there they were located in the gallery of the market. Vossius, reports S. Ackerman, took the manuscripts due to him from there. According to her,their appearance was not very attractive (They are not lavish presentation copies but rather are plain copies …). There is evidence that, apparently, Vossius was going to exchange them for other manuscripts that interested him.

However, what exactly (and why) went to Vossius is not fully understood. According to S. Ackerman, this could be the object of further research.

We need this information in order to try to find out one of the most important circumstances in the history of the Silver Codex: was it among the manuscripts from the collection of Rudolph II that Vossius inherited?

Firstly, the SA is not an essay on alchemy, but on a completely different topic. Secondly, the appearance of all the “Prague” alchemical manuscripts of Vossius is very unsightly, and they are “simple copies”, while the SA can in no way be said to be a “simple copy”. Thirdly, the alchemical manuscripts of Vossius date back to the end of the 16th century …

All this suggests that the SA would be a “black sheep” among the manuscripts that make up the “pay” to Vossius. But the Verdun manuscript – if it was a simple copy, and not Codex Argenteus – could get into their company. Although, most likely, BP was not included in the “fee”; if it was a simple copy, then most likely they did not attach much importance to it, and Vossius could well just take it “for a while” from the collections of books and manuscripts of Queen Christina.

Francis Junius, Derrer, and Marshal Count de la Guardie

Let us return again to Metzger’s story quoted above about the history of Codex Argenteus.

We learned from it that Vossius showed the manuscript to his uncle Francis Junius, a connoisseur of ancient Teutonic languages. Seeing the translation of the Gospels into the “Gothic language”, Junius considered this the finger of Providence; realizing that the manuscript is a unique document, he began to prepare

“the first printed edition of the version of the Gospels of Ulfilah (Dordrecht, 1665).” Here we will not touch upon the problem of whether the versions of the Gospels contained in Codex Argenteus can be considered versions of Ulfilah; it would be more accurate to say that this was the publication of the Gospels from a manuscript in the same “Gothic language”.

As it turns out from the words of Metzger, this edition required a “transcription” of the text of the manuscript. In other words, a list was made – most likely, more clear and legible. Unraveling the handwriting of the scribe of the manuscript had a scientist named Derrer.

And here in the history of the Codex appears the Swedish Marshal Count de la Guardie. According to Kulundzhich, he bought a manuscript from Vossius, then ordered a silver binding for her (therefore, understood its value) and then presented it to the queen.

Yes, most likely, the marshal gave Queen Christine exactly Codex Argenteus – the manuscript that is now in Uppsala. This is really a royal gift.

But what did he buy from Vossius? Verdun manuscript? Apparently not. The logic of facts leads us to the following hypothesis: The

Swedish Marshal Count de la Guardie bought – or, rather, ordered – a “royal” list from the Verdun manuscript; high quality parchment list, made at the best level of calligraphy of that time, using advanced technologies for that era. The list, which is a real work of art, which is worthy to perpetuate the text of the Verdun manuscript, and which is worthy to become a gift to the queen. This list is Codex Argenteus.

The further fate of the Silver Code is also logical. Is Derrer its creator? Perhaps further research will answer this question.

Dating: XVII century

. The analysis of the history of the Silver Code carried out here gives many reasons in favor of the hypothesis formulated above about its creation. However, this analysis does not prove it. It remains likely (according to the author of these lines is very small) that the traditional version attributing the creation of SA to the masters at the court of King Theodorich in Ravenna is true.

In addition, the use of glass vessels in alchemy, which began in the 1620s, created the potential for separate “technological breakthroughs”: someone from the circle of alchemists close to Glauber could create an analogue of ink for “silver letters” shortly after 1620 . This means that it cannot be ruled out that the “royal list” with the Verdun manuscript — silver and gold letters — was made, for example, between the years 1648 and 1654 at the court of Christina in Stockholm, or even somewhat earlier, in Prague , in the Khradchansky castle. But, given the pace of development of alchemical knowledge and alchemical practice, the probability of a manuscript like the Silver Code at the beginning of the period 1620-1660 should be assessed as small; it rises sharply towards the end of this period, i.e. by 1660.

Thus, based on these considerations, we propose the following dating of the Silver Code: the probability that it was created before 1620 is close to zero; starting from 1620, this probability increases and reaches a maximum around 1660, when the existence of the code is not in doubt.

Figures 4 and 5 show what a manuscript of the early 16th century looks like with a golden letter close-up.

Figure 4. Early 16th century manuscript |

Figure 5 Golden letter (enlarged) |

Acknowledgment

I am grateful to A. Safonov for useful information.

Comments

one it fell into their hands together with the other treasures of the Imperial Castle of Hradcany. It was subsequently deposited in the library of Queen Christina in Stockholm, but on the abdication of the Queen in 1654 it was acquired by one of her librarians, the Dutch scholar Isaac Vossius. He took the manuscript with him to Holland, where, in 1662, the Swedish Count Magnus Gabriel De la Gardie bought the codex from Vossius and, in 1669, presented it to the University of Uppsala. He had previously had it bound in a chased silver binding, made in Stockholm from designs by the painter David Klocker Ehrenstrahl. ”

назад >>>

Цитированная литература

БРО Брокгауз, Ф.А. и И. А. Ефрон. Энциклопедический словарь. Алхимия.

http://www.cultinfo.ru/fulltext/1/001/007/121/

http://www.cultinfo.ru/fulltext/1/001/007/002/2383.htm

КЕС Кеслер, Я. Русская цивилизация. Эко-Пресс 2000, Москва, 2002.

МЕЦ Мецгер, Брюс М..Ранние переводы Нового Завета. Библиотека Католической информационной службы “Agnuz”. http://www.agnuz.info/library/books/mecger_rannie_perevodi/index.htm

СОБ Соболевский, А.И. Славяно-русская палеография. Санкт-Петербург, 1908. – электронная версия – http://www.textology.ru/drevnost/sobolevsky.html

ТОБ Тоботрас А. История Праги. http://www.prag.ru/history-prag/history-prag-7.html

ЧИЛ Чилингиров, А. Готи и Гети. Ziezi ex quo Vulgares, София, 2005.

ШУМ Шумах, И. Порох и кислота. Электронный альманах Арт&Факт №2, 2006. http://artifact.org.ru/content/view/15/70/

AKE1 Akerman, S. Christina of Sweden (1626-1689), the Porta Magica and the Italian poets of the Golden and Rosy Cross. http://www.alchemywebsite.com/queen_christina.html

АКЕ2 Alchemy Academy archive September 1999. http://www.levity.com/alchemy/a-archive_sep99.html

DAV Davis, G. Codex argenteus non lingua gotorum verum lingua gotica. Journal of Language and Linguistics. Vol. 1 No. 3 2002, 308-313. http://www.shakespeare.uk.net/journal/1_3/DAVIS.DOC

KUL Kulundzic, Z. .Knjiga o knjizi. I tom: Historija pisama (Volume 1. History of Writing). Zagreb, 1957.

MAR Статья о книге П. Маршалла: Peter Marshall, ‘The Theatre of the World, Alchemy, Astrology and Magic in Renaissance Prague’, Harvill Secker, 2006. http://travel.independent.co.uk/europe/article1778374.ece

MUNK1 Lars Munkhammar. Codex Argenteus – The Silver Bible. PA SVENSKA, 1998-08-12.

http://www.ub.uu.se/arv/codexeng.cfm

MUNK2 Munkhammar, L. Codex Argenteus, From Ravenna to Uppsala, The wanderings of a Gothic manuscript from the early sixth century. 64th IFLA General Conference August 16 – August 21, 1998. Conference Programme and Proceedings. http://www.ifla.org/IV/ifla64/050-132e.htm

TOP Topper, U. Falschungen der Geschichte. Herbig, Munchen, 2001.